The Sexuality in “Asexuality”: Building Intentional Relationships

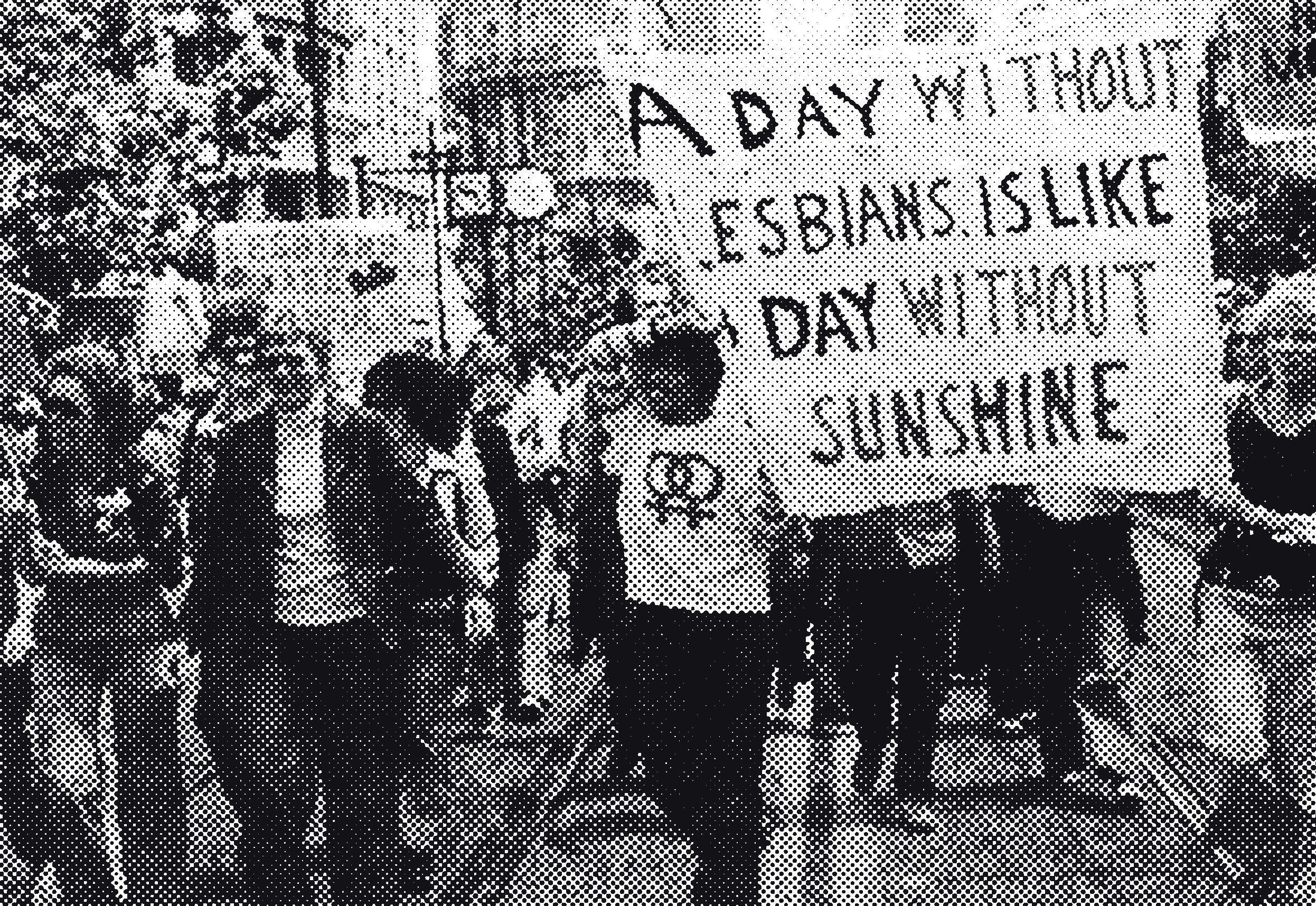

Radical romantic redefinitions are often associated with Queer Platonic Relationships (QPRs) and Polyamory. A-spec identities (those on the spectrum of asexuality and aromaticism) are frequently the unacknowledged core of these, rarely recognised for the radical acceptance and resistance required for the formation of a happy, a-spec life.

Many of us are familiar with the idea that queer joy is a fundamental part of resistance. Joy on the asexual spectrum involves not only rewriting who you are attracted to, but how you are attracted, how you do or don’t experience love and affection and desire, and how you relate to these concepts and ideals in society. Figuring out an aspec identity involves massive, intentional reflection, not only of your romantic or sexual attraction but platonic, aesthetic, and how each of these contributes to fulfilling your needs and desires.

Up until I started to make friends with other asexual people, the only ace representation I had seen was bookish, quiet, and entirely uninterested in romance or dating or sex. While some of that does resonate with me, it never really felt right. I love romance, even in my platonic relationships. I delight in sharing close, intimate relationships with people, and in making people happy even when I don’t know them. And as I grew into my 20s, I loved meeting people, flirting, dancing, kissing, I formed wonderful, caring, long-term friends with benefits relationships, I would stay out clubbing until the sun came up, and I went to sex-on-prem events. It just didn’t fully occur to me that this could all exist in a happy asexual life. For me, this realisation prompted a complete overhaul, not just of my actual needs and desires, but of the ways I had been taught to understand and communicate my thoughts, needs, and desires.

The sex I had wasn’t always, but was often traumatic to some extent. I couldn’t entirely understand why until I started exploring my asexuality more intentionally. I didn’t have sex because I thought that was just what people did, or because I didn’t know what asexuality was. I was having sex because I liked the kissing, the cuddling, and the closeness, and at that point in my life, sex felt like the simplest way to access that level and form of intimacy.

Even though I already knew a lot about asexuality and aromanticism, it didn’t really occur to me that I would be able to meet someone and structure a relationship in such a way that I was supported and loved and satisfied in the ways that were important to me. It definitely didn’t occur to me that this process didn’t have to be scary and painful, but could instead be an understanding, loving, and patient one.

It’s like I was playing golf because I really liked the lunch options and the dress code at the course clubhouse – I didn’t really care either way for the golf, I just liked dressing up and having a good lunch with a good mate on a golf course, and socially speaking, golf was the simplest way to do that. That is until a close asexual friend of mine encouraged me to really interrogate what I enjoyed and why I enjoyed those things, and helped me explore what actually worked for me. This friend was instrumental in helping me realise the full extent of my queerness, and ultimately I might not have known enough about myself to hit it off with my now partner if that friend hadn’t been so open to talking about asexuality.

My partner also had a large part to play, of course. It’s one thing to say “alright, so I enjoy these bits of casual sex, and not so much the rest of it”. It’s an entirely different ballgame to build a relationship, from scratch, with someone else who doesn’t subscribe to social pressures around relationship expectations. A relationship where we said “I love you” three months before, and two days after we first kissed. Where we shared a bed and discussed our needs and wants for romantic relationships before we started dating. Where we are open and direct about our needs and our expectations. Where we don’t have what most people would recognise as sex, but we are both more comfortable and satisfied than ever before. Where we recognise that our friends can be just as important to us as each other, and we depend on our social circle to meet some of our emotional and support needs. This level of intentionality and communication was very new to me. And it was essential in understanding myself, because aspec identities are a spectrum for a reason; there are no two entirely the same. We all have different likes and dislikes, different levels of sexual and romantic attraction, and different things we need out of our relationships. The only way to understand your own is to learn about others’ identities, and lovingly explore your own.

This is not to imply that discovering the full extent of your queerness is never traumatic. It not only means letting go of old goals and dreams and versions of yourself, but realising how much of your life was forced onto you by social norms, or by misunderstanding family or partner, or by yourself in a misguided attempt to be happy or fit in. The process of getting to know yourself better comes accompanied by grief. For me, it meant realising how much of my sex life was traumatic in some way, and how much I had mangled myself and my needs in order to have what society deemed a worthy relationship. And most importantly, realising that wasn’t an indicator of how the rest of my life had to go.

Where to

find support

Looking for someone to talk to?

Find peer groups, community organisations and referral pathways for LGBTIQ+ women and gender diverse people.