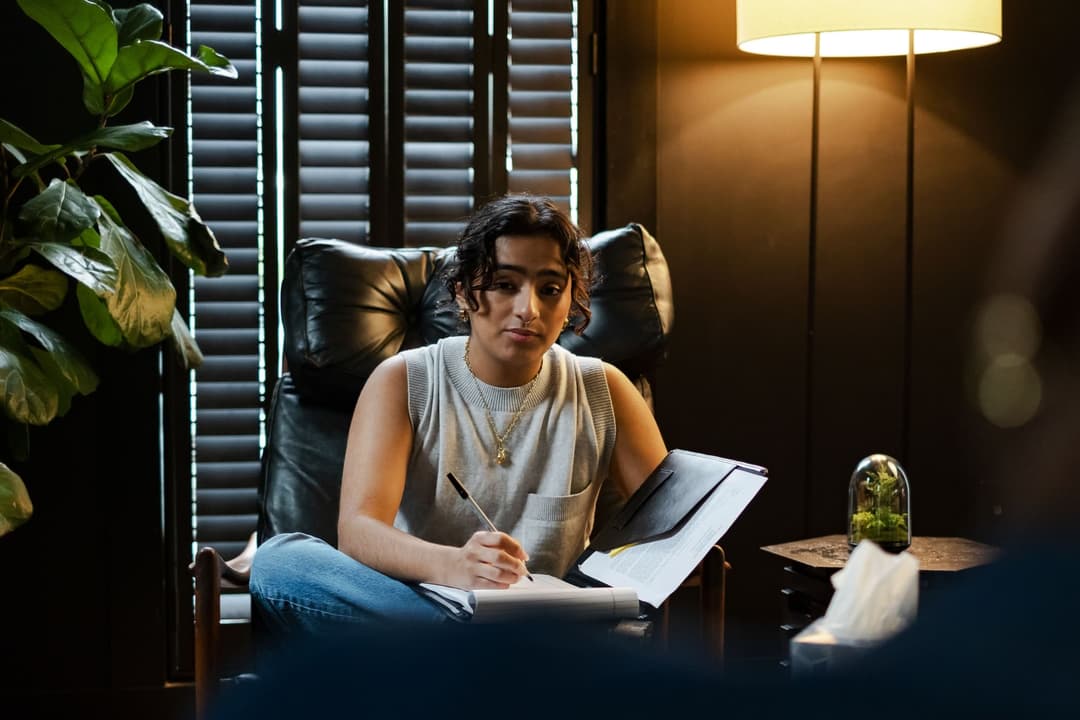

Finding Freedom Through Neurodivergent and Queer Authenticity

When speech pathologist Frances Brennan started her own clinic, she didn’t intend to become a leading voice for neurodivergent and queer inclusion. But that’s exactly what happened with The Speech Tree, a leading paediatric and adolescent speech pathology clinic dedicated to providing neurodiverse affirming care. Frances chatted to us about The Speech Tree, the intersection of being queer and neurodivergent, and the importance of doing things a little differently.

How did The Speech Tree start?

‘I never planned to go into business. I had an idea one night, and within 24 hours, I’d drawn up a logo and written my resignation letter. It was terrifying, but I knew I couldn’t keep trying to fit into systems that weren’t built for people like me.’

For Frances, who is neurodivergent and queer, that leap into self-determined practice was more than a career change. It was a step toward authenticity – a theme that underpins her work.

Redefining Speech Pathology and Connection

‘Speech pathology is widely misunderstood. People think we just help kids who say ‘wascally wabbit,’ but we work on so much more – communication, literacy, swallowing, social connectedness, even navigating school or preparing for job interviews.’

Frances’s approach departs from traditional ‘social skills’ models, which often pressure autistic people to appear more neurotypical. Instead, she focuses on helping clients succeed as they are.

‘We’ve moved away from trying to ‘fix’ people. My work is about acceptance – recognising that there’s no one correct way to communicate or connect.’

That ethos grew naturally from her own experiences. Early in her career, Frances found herself drawn to autistic clients others described as ‘difficult.’

‘I’d meet these kids and think, they’re awesome. I realised I connected with them because I understood them – and because, in many ways, I was them.’

Unmasking the Hidden Costs of Conformity

Frances describes the years before her diagnosis as marked by a constant effort to ‘mask’- to blend in and perform the version of herself that others expected.

‘Masking is when neurodivergent people suppress natural behaviours or mirror others to fit social norms. It’s being a chameleon. You learn to give people exactly what they want, even if it costs you your sense of self.’

The toll is profound.

‘When you’ve been doing it since childhood, you eventually ask, Who am I really?” That’s when you see mental health issues – anxiety, depression and self-doubt emerge.’

Frances knows this firsthand.

‘At one point, I was even misdiagnosed with borderline personality disorder. It was devastating – it made me question my worth. Later, when a professional recognised, I was actually autistic, everything finally made sense.’

For Brennan, masking isn’t simply about hiding traits – it’s about survival in a world that punishes difference.

‘From a young age, we’re told to ‘sit still and listen,’ even though, for some of us, sitting still means we can’t listen. You’re constantly told what feels right to you is wrong.’

That disconnect can be exhausting, she says, particularly when layered with gender and sexuality.

‘Being autistic, you already question what’s real or performative about your identity. Add gender into the mix – something abstract and social – and it becomes incredibly complex.’

The Intersection of Queerness and Neurodivergence

In recent years, Frances has become increasingly open about her queer identity, recognising how deeply it intersects with her neurodivergence.

‘For a long time, I didn’t talk about being queer – it didn’t seem relevant. But then I realised, for many of my clients, it’s everything.’

She sees growing numbers of gender-diverse young people in her clinic, many of whom are also autistic.

‘Statistically, autistic people are much more likely to be gender diverse. These people are navigating multiple layers of identity while also learning to self-advocate in systems that don’t understand them.’

That advocacy work extends to families and schools.

‘I spend a lot of time educating others that gender and neurodiversity are not phases or copycat behaviours. These young people are simply trying to find themselves – and they need validation, not scepticism.’

Frances’s own exploration of gender has been similarly reflective.

‘I’ve always used she/her pronouns, but lately, I’m finding that she/they feels more accurate. But as an autistic person, you second-guess everything – what’s authentic, what’s masking. It’s hard to untangle.’

Community, Connection and Belonging

Despite the challenges, they say that finding community among other neurodivergent and queer people has been transformative.

‘I used to think of being queer and being autistic as two separate minorities I belonged to. Now I realise there’s a super-minority in the middle, and that’s where I’ve found my people.’

When she meets others who share both identities, ‘there’s an instant sense of understanding. It’s like, you’re my person. Communication flows differently; it’s comfortable, intuitive. That’s where the healing happens – after years of trying to fit into a neurotypical world.’

She encourages others to seek out similar spaces.

‘There aren’t many organisations specifically for queer autistic people yet, but they overlap. You’ll find queer people in autistic spaces and autistic people in queer spaces. Sometimes it’s as simple as wearing a badge or pin that signals who you are – people recognise it.’

They work closely with Yellow Ladybugs, a support organisation for autistic girls, women and gender-diverse youth.

‘It’s a beautiful community – safe, inclusive, and affirming.’

A Call for Authenticity – and a New Kind of ‘Normal’

Looking ahead, Frances hopes for a world where no one has to constantly ‘come out.’

‘I feel like I’m always coming out – as gay, as autistic, as ADHD. I drop it into conversation to explain myself, almost apologetically. I’d love for that not to be necessary.’

She envisions a society where difference isn’t a revelation but an ordinary fact of life.

‘I want us to be just another type of ‘normal’, not a subgroup that needs explaining.’

And yet, she acknowledges the paradox of conformity.

‘There’s comfort in belonging, conformity isn’t always bad; sometimes it’s how we find our community.’

Embracing the ‘Neurospicy’ Life

Frances’s message is consistent: authenticity heals.

‘When you finally stop pretending and start embracing who you are – whether that’s queer, autistic, or both – it’s liberating.

‘And that’s what I want for the next generation: to not just survive a world that wasn’t built for them, but to reshape it.’

For more about Frances Brennan’s work head to thespeechtree.com.au or follow The Speech Tree on Instagram and TikTok.

For more on Yellow Ladybugs, head here yellowladybugs.com.au

Where to

find support

Looking for someone to talk to?

Find peer groups, community organisations and referral pathways for LGBTIQ+ women and gender diverse people.