Joan Nestle: Desire, Memory and Belonging

At 85 years old, Joan Nestle still speaks with the fire of someone who has never stopped believing in love, in justice, and in the power of stories. She is a writer, activist, archivist, community elder and cancer survivor. Nestle has spent a lifetime preserving lesbian histories, fighting against erasure, and celebrating desire in all its messy, complicated, beautiful forms.

A Childhood in the Bronx

Joan was born in the Bronx in 1940, the daughter of Jewish immigrants making their way in America. Her father died before she was born, so her mother raised her and her brother Elliott as a single parent in a small apartment, working as a bookkeeper to keep them afloat. It was a childhood defined by both hardship and strength.

‘I knew the word deceased before I knew many other words,’ Joan says. ‘It was stamped on my father’s papers. I learned early what it meant to live with loss.’

By her teens, Joan knew she was different. In the 1950s, difference carried risk. The McCarthy era cast suspicion on anyone seen as subversive – communists, queers, radicals. Teachers lost jobs, neighbours whispered, bars were raided.

And yet, desire spoke louder than fear. At 15 she began sneaking into Greenwich Village, following butch–femme couples through the streets, reading coded pulp paperbacks that doubled as pornography and survival manuals.

Her first moment of recognition came in a dingy café where young queer people gathered.

‘It was a homecoming,’ Joan says. ‘It was terror, gratitude and overwhelming desire all at once.’

Those bars were far from safe. Police raids could end in humiliation or arrest. Bashers waited outside. Yet they were also classrooms, family rooms, sanctuaries.

‘They taught me how to live,’ Joan said. ‘There were rules and codes, but there was also joy – the joy of finding one another.’

She describes the butch–femme world not as imitation, but as invention: a way to script relationships and sexualities when mainstream society offered nothing but shame.

‘We were making our own language,’ Joan explains. ‘It was creativity under fire.’

Learning from Liberation

By the late 1960s and early 70s, Joan was already shaped by more than queer bars. She had marched in Selma, a series of civil rights protests in Alabama in 1965, where activists marched from Selma to Montgomery to demand equal voting rights for Black Americans, she worked on voter registration in the South and lived among communities who understood state repression.

That experience fed directly into her work with the Gay Academic Union, where she was a co-founder. Even in that radical space, she joined a socialist caucus with thinkers like Jonathan Katz (author of The Invention of Heterosexuality) and Gayle Rubin (cultural anthropologist and pioneer of feminist and queer studies), constantly pushing boundaries.

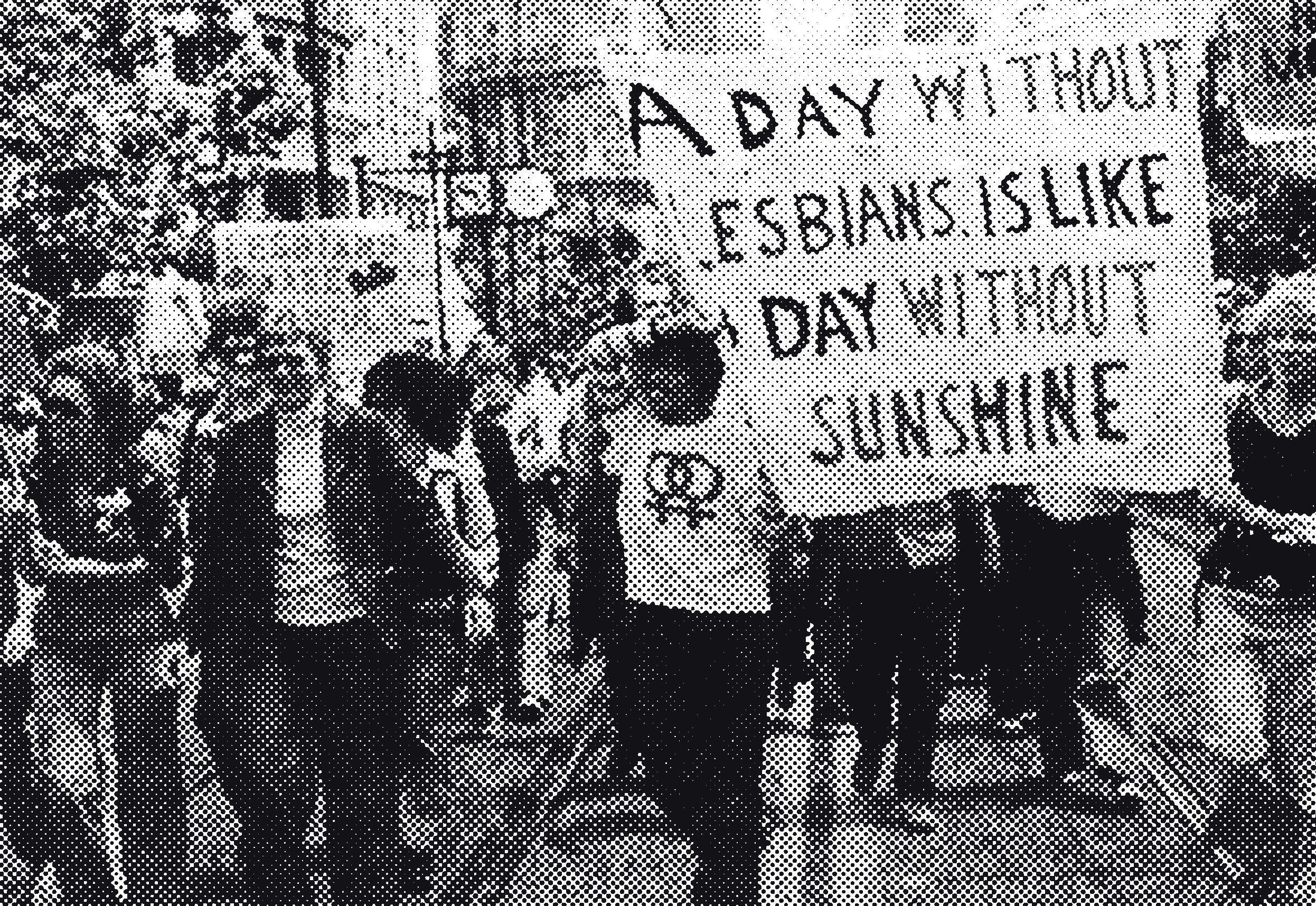

Meetings were sometimes disrupted by bomb threats. Inside, women formed consciousness-raising groups. Out of those small, intimate sessions, the idea for the Lesbian Herstory Archives was born.

‘We were already losing artefacts of lesbian life,’ Joan said. ‘Magazines, newsletters, photographs – grassroots things that would vanish if we didn’t save them. We decided: we will not be erased. We will build our own memory.’

The Archives: Memory as Resistance

The Archives began in Joan’s Upper West Side apartment in 1974. Visitors buzzed the door, stepped past her washing line, and entered a space stacked with boxes, files, and treasures.

‘It was domestic and political at the same time,’ Joan says. ‘The kitchen table was our catalogue desk. People brought shoeboxes of photos, love letters, bar matchbooks. We kept it all. We knew each scrap mattered.’

The guiding principles were radical: the collection would be free to all, controlled by the community, not by universities or institutions. Anyone could walk in and read their own history.

One of her favourite donations came from older lesbians who brought in ‘house books’ – informal journals kept by women in shared households before mobile phones, noting calls, visitors and gossip. ‘Younger generations love those,’ Joan says. ‘They see everyday queer life, the intimacy, the humour. It makes history real.’

Today, the Archives live in a Brooklyn brownstone, still open to all. For Joan, it remains her proudest legacy:

Pull quote

‘We turned deprivation into plentitude. We took what was meant to disappear and made it last.’

Writing Desire

At the same time, Joan’s writing gave voice to lesbian lives too often shamed or ignored. A Restricted Country (1987) wove memoir with political reflection, giving readers a glimpse into her working-class childhood, her queer coming of age, and her activism. The Persistent Desire (1992) became the definitive collection on butch–femme sexuality.

But her insistence on writing about sex provoked backlash. During the feminist sex wars of the 1980s, Joan and her peers – Gayle Rubin, Dorothy Allison, Amber Hollibaugh – were accused of ‘perpetuating patriarchy’ by celebrating S/M or butch–femme roles.

Conferences disinvited her. Protesters waved placards with her name on them. Even within feminist spaces, she was told her writing had no place.

Her answer was to double down.

‘I knew about women’s victimisation – I saw it on my mother’s face, in her broken teeth. But I also knew there was a sexual call to life. When people told me I wasn’t allowed to write that, it only made me more determined.’

Her essay ‘My Mother Liked to Fuck’ was her act of defiance – uniting her mother’s survival from sexual abuse with her own sexual honesty. It travelled around the world, reminding lesbians that their desire was not shameful, but powerful.

From New York to Melbourne

At 61, Joan’s life changed again. She moved to Melbourne with her partner, human rights lawyer Di Otto. The decision was rooted in love but complicated by Joan’s medical history. Having survived breast and colon cancer, she was almost denied residency.

Joan was placed on the ‘unwanted’ list.

‘We’d given up our New York home, flown across the world, and I didn’t know if I’d even be allowed to stay,’ she remembered. ‘It was a cruel irony – I had survived cancer, but now cancer threatened to exile me from love, from the life I was building.’

It was only through the support of Di and a gay immigration lawyer that she was eventually granted the right to remain.

‘That moment taught me how precarious belonging can be. Illness makes you vulnerable not just in your body, but in the eyes of the state. Waiting to see if I’d be allowed to stay taught me so much about the fragility of belonging.’

She was eventually granted residency, and the move transformed her.

‘New Yorkers can be so provincial. Coming here made me international. I learned new histories, new languages, new skies.’

Australia also confronted her with new truths. Attending her first Welcome to Country ceremony, she realised she had never known the name of the Indigenous people whose land she grew up on in the Bronx.

‘That’s what this country gave me – the knowledge that history always surrounds us, if we listen.’

Illness and Intimacy

When she was first diagnosed with breast cancer in New York, she resisted the impulse to see herself as broken. Instead, she leaned on the same instincts that drove her to preserve lesbian histories: the knowledge that what is scarred can still be beautiful, and that survival itself is a form of testimony.

Joan has survived three cancers – breast, colon and uterine. Illness became another layer in her philosophy of erotic honesty.

She wrote about sex after cancer in an essay called My Cancer Travels, urging partners not to fear scars.

‘It was a plea – to be touched in the old way. To be loved without fear.’

For Joan, her scars were not signs of shame but of survival. Her body remained a site of desire, even after illness.

‘I wanted to name it – the loneliness of being seen only as a patient. I wanted to say: I am still here, I am still whole, I am still a woman who wants to be kissed.’

Her writing about cancer, like her writing about sexuality, broke silences. It pushed against shame and demanded that readers hold complexity: pain alongside pleasure, frailty alongside desire.

‘I joke that I’m layered not just in histories, but in cancers,’ she says. ‘The scars are maps now. They tell stories too.’

‘I wrote about it as part of my archive,’ Joan recalled. ‘My body was another document. The surgeries, the scars, the fear – they were all entries in the story of who I am.’

Lessons in Mortality

At 85, Joan sees cancer less as an enemy she fought and more as a stern teacher.

‘Cancer made me look mortality in the face,’ she said. ‘It asked me: what will you do with the time you have left? And my answer was the same as it has always been – tell the stories, hold the memories, love the people.’

She doesn’t romanticise it. Treatment was brutal, the fear constant, the costs high. But she refuses to let cancer define her life. ‘Yes, I’ve had cancer. But I’ve also had joy, and love, and community. If you only see me as a survivor, you miss the rest of the picture.’

[My scars] remind me of the body’s stubbornness, of its ability to keep going,’ she said. ‘And they remind me of the generosity of those who stayed beside me – lovers, friends, comrades. Survival is never solitary.’

In this way, cancer fits seamlessly into her larger philosophy: that queer life is about refusing exile, whether from history, from pleasure, or from one’s own wounded body.

The Next Generation

Now in her mid-80s, Joan is a patron of the Australian Queer Archives. She delights in the energy of younger queers who have a renewed interest in the Archives.

‘Young people keep my words alive,’ she said. ‘They want to know our stories, even if they speak a different language. That’s how we know we were here. That’s how we know we mattered.

‘What appeals to one generation isn’t what appeals to another. But if we listen, we find traces of each other. That’s how community is built.’

Her advice in a time of rising authoritarianism is clear:

‘It is never too small a gathering to begin. Talk to each other. Be in the streets. Keep writing, keep singing, keep holding each other. That’s how we fight despair.’

A Living Archive

Joan Nestle is many things: writer, activist, archivist, teacher. But perhaps most of all, she is a living archive herself – carrying the songs, desires, and struggles of generations within her, and passing them on to those who come next.

At 85, her body carries scars, her voice carries history, and her presence carries hope. Listening to her is like stepping into a room filled with both memory and possibility – a reminder that we are never alone, and that the fight for joy is always worth it, but she is also quick to remind us:

‘I’m not a hero. I’m just someone who refused exile. And that’s what I want others to do – refuse exile, in whatever form it comes.

‘I have also learned that sometimes exile, the ability to stand outside the offered embrace of a community, is necessary as I learned throughout my struggles during the McCarthy years, the sex war years, and for many years now as a Jew opposed to Israel’s occupation of Palestine, but I have always found I was not alone, that exile leads to new lands.

‘Keep writing. Keep singing. Keep marching. Keep touching each other with love,’ she says. ‘The world will try to silence us again and again. But if we hold on to joy, to each other, we will survive.’

Where to

find support

Looking for someone to talk to?

Access safe (and pre-screened) health from our resource list.